Chiến dịch Wayne Grey là một chiến dịch được thực hiện bởi lữ đoàn 1, Sư đoàn Bộ binh 4 Mỹ và các lực lượng hỗ trợ, từ ngày 1 tháng 3 đến ngày 14 tháng 4 năm 1969. Mục tiêu chính của chiến dịch là cắt đứt các tuyến liên lạc và cung cấp cho các Trung đoàn Bộ binh 24 và 66 của Quân đội Nhân dân Việt Nam (PAVN) cũng như ngăn chặn họ rút lui vào Campuchia.

Mở đầu

Các tài liệu bị bắt giữ và các cuộc thẩm vấn đối với tù binh đã tiết lộ rằng vào cuối tháng Giêng đến đầu tháng Hai, Trung đoàn 66 và Trung đoàn 24 và các đơn vị của đoàn Pháo binh 40 thuộc CSBV đã di chuyển về phía bắc vào khu vực núi Chu-Mom-Ray và đã bắt đầu thực hiện các hoạt động tấn công. Trinh sát trên không đối với các căn cứ ở phía tây Trại Polei Kleng đã phát hiện ra lưu lượng xe cộ dày đặc và việc xây dựng các con đường sâu vào các núi Chu-Mom-Ray và từ biên giới Campuchia vào thung lũng Plei Trap phía đông. Việc xác nhận sự hiện diện của pháo binh và khả năng có các đơn vị thiết giáp của địch cho thấy một cuộc tấn công lớn đang được lập kế hoạch và có khả năng cao nhắm vào thị xã kontum và trại Polei Kleng.

===

Chiến dịch Wayne Grey bắt đầu vào ngày 1 tháng 3, khi đại đội (đ.đ.) A của Tiểu đoàn 3, Trung đoàn 12 Bộ binh từ Polei Mrong đã được trực thăng đổ xuống bãi đáp hay LZ Swinger (14.429°N 107.627°E). Mục tiêu của họ là bảo vệ LZ và thiết lập một vị trí pháo để đặt súng. Vị trí này sẽ được dùng để hỗ trợ các TĐ 3/12, 1/8 và 3/8 Bộ binh khi họ thực hiện các hoạt động ở Plei Trap. Trực thăng đầu tiên đã hạ cánh và đổ quân một cách an toàn. Sau khi trực thăng thứ hai bắt đầu đổ quân, họ đã bị tấn công bởi đặc công từ TĐ công binh K25B của Quân đội Nhân dân Việt Nam. Cuộc giao tranh ban đầu kéo dài hơn ba giờ trước khi quân csbv rút lui và đơn vị thuộc 1/92 Pháo binh Dã chiến đã có thể đáp xuống và thiết lập các khẩu pháo của họ. Đại đội B của 1/8 đã tấn công vào căn cứ hỏa lực (CCHL) 20 (14.492°N 107.597°E) và đại đội C của 3/8 tấn công vào Firebase Pause (14.36°N 107.655°E), sau đó là các Công ty A và C của Trung đoàn 6/29. Trung đoàn 6/29 hiện đã vào vị trí để hỗ trợ cuộc lùng sục của Lữ đoàn 1 tại Plei Trap. Vào ngày 2 tháng 3, Công ty A, 1/8 đã giành được LZ Turkey (14.474°N 107.598°E) và bắt đầu các hoạt động do thám, trong khi các Công ty C và D, 1/8 tấn công vào LZ Susan (14.49°N 107.54°E). Các công ty còn lại từ 3/8 đã được triển khai tại các LZ ở và quanh LZ Mary (14.386°N 107.578°E).

Giai đoạn I

Các hoạt động dọc theo đường Plei Trap được thực hiện bởi các Công ty A, C và D, Trung đoàn 1/8 Bộ binh. Bắt đầu từ ngày 1 tháng 3, với sự hỗ trợ của A/7-17th không kỵ, trung đoàn 1/8 đã có thể xác định và tiêu diệt các liên lạc, vật tư và phương tiện dọc theo đường Plei Trap, cũng như tái thu hồi hai khẩu lựu pháo M101 bị PAVN bắt giữ.

Trận đánh tại Khu đất Hạ cánh Brace là trận đánh lớn nhất và quan trọng nhất của chiến dịch. Nó bắt đầu vào ngày 3 tháng 3 khi Đại đội A, tiểu đoàn 3/8 Bộ binh, liên lạc với một tiểu đoàn quân PAVN tại tổng hành dinh của họ trên đỉnh một ngọn đồi (14.345°N 107.605°E). Đại đội A phải chịu nhiều thương vong trong trận đánh và buộc phải rút lui. Họ được rút ra vào ngày 4 tháng 3 sau những trận giao tranh ác liệt tại vị trí đêm của họ. Các Đại đội B và C, tiểu đoàn 3/8, đã thành công trong việc chiếm giữ ngọn đồi vào ngày 6 tháng 3.

Một firebase đã được xây dựng sau khi LZ, bây giờ được gọi là Brace, đã được bảo đảm và vào ngày 16 tháng 3, công ty C, 6/29 thuộc pháo binh đã được đặt tại đó cùng với phần còn lại của công ty A, 3/8 và tổng hành dinh 3/8.

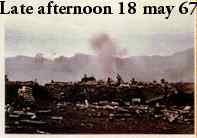

OP Wayne Grey Di chuyển IIIOP Wayne Grey Di chuyển IIIOP Wayne Grey Di chuyển IVOP Wayne Grey Di chuyển IVĐồi 947 (14.337°N 107.604°E) đã được thành lập vào ngày 3 tháng 3 bởi công ty D, 3/8 bộ binh để chặn PAVN rút lui từ LZ Brace. Vị trí này đã bị tấn công nhiều lần giữa ngày 3 và ngày 8 tháng 3 cũng như phải đối mặt với các cuộc tấn công bằng cối và pháo binh liên tục. Công ty D đã thành công trong việc giữ ngọn đồi trước các cuộc tấn công của PAVN và đến chiều ngày 8 tháng 3, PAVN đã từ bỏ nỗ lực chiếm giữ vị trí này.Vào ngày 7 tháng 3, công ty D đã di chuyển qua đất liền đến Firebase 20 để hỗ trợ công ty B trong các cuộc tuần tra nhằm giúp một cuộc tuần tra tại đồi 1030. Các công ty A và C tiếp tục hoạt động dọc theo con đường Plei Trap.Giữa ngày 10 và 14 tháng 3, Lực lượng tác chiến Swift gồm các Công ty B và D, 3/12 cùng với một đại đội trinh sát, đã củng cố vị trí tại đồi 947. Vào ngày 11, Swift đã tiếp xúc với một công ty PAVN và rút về vòng ngoài để yêu cầu không kích B-52; họ lại tiếp tục bị bắn phá bằng đạn cối. Hôm sau, họ đã tấn công và chiếm giữ vị trí của PAVN.Vào ngày 17 tháng 3, các công ty A và C đã thành lập một căn cứ tuần tra mới từ Đồi 467 để tiến hành các cuộc tuần tra chung dọc theo các tuyến liên lạc của PAVN và ngăn chặn dòng chảy cung cấp cho pháo binh 40.[1][3]Giai đoạn IILực lượng tác chiến AlphaSau khi các công ty A và C đã xác định và tiêu diệt một lực lượng PAVN ở phía nam Đồi 467, họ đã tổ chức lại thành Lực lượng tác chiến Alpha vào ngày 17 tháng 3. Nhiệm vụ của họ là thiết lập các vị trí chặn có quy mô công ty giữa căn cứ của họ tại Đồi 467 và Firebase 20, với mục tiêu cắt đứt nguồn cung cấp và tăng viện của PAVN trong khu vực. Các thiết bị phá hủy cũng được sử dụng để làm tê liệt các hoạt động dọc theo con đường Plei Trap bằng cách biến nó thành không thể đi qua cho các phương tiện.Các hoạt động tiếp tục trong khu vực cho đến ngày 30 tháng 3, QLVNCH sử dụng súng cối và pháo binh chống lại các căn cứ hỏa lực của Sư Đoàn 4 trong khu vực và gửi truyền đơn tuyên truyền kêu gọi binh lính Hoa Kỳ đầu hàng. Lực lượng Đặc nhiệm Alpha được rút ra vào ngày 30 tháng 3. [1][3]

Núi Cu-Đôn

Cu-Don là một căn cứ nổi tiếng của QLVNCH nằm trên một sườn núi phía nam LZ Brace và bị nghi ngờ là điểm rút lui của Trung Đoàn 66 Bộ binh QLVNCH. Nhiệm vụ của Sư Đoàn 3/12 là ngăn chặn và quấy rối QLVNCH rút lui. Vào ngày 14 tháng 3, Đại đội A và C cùng với một trung đội trinh sát, tấn công vào LZ Cider (14,278°B 107,617°E) để bảo vệ nó làm căn cứ hỏa lực cho Khẩu đội B, pháo binh 6/29. Đại đội D bảo vệ LZ D-Handle (14,33°B 107,609°E) để đặt súng cối 4,2" và Đại đội B di chuyển trên đường bộ đến một căn cứ tuần tra tại YA818856 (14,328°B 107,612°E). Liên lạc mạnh mẽ được thực hiện vào ngày 18 tháng 3 khi Đại Đội D tiếp xúc với một tổ hợp boongke của QLVNCH. Liên lạc đã bị phá vỡ và pháo binh cùng cối đã được gọi đến. Ngày hôm sau, vị trí bị bao vây bởi hỏa lực pháo binh và máy bay chiến đấu cả ngày. Vào ngày 20, Đại đội D đã cố gắng tấn công các hầm hào với sự hỗ trợ của pháo binh và không quân, nhưng đã bị lực lượng phòng thủ đánh bật. Đại đội D đã phải rút về LZ D-Handle. Vào ngày 22, sau một đợt pháo kích mạnh, Đại đội D đã chiếm lấy đồi mà không gặp phải sự phản kháng nào. Vào ngày 27, Đại đội A đã có liên lạc gần LZ Cider và đã buộc phải ngắt liên lạc sau khi bị bắn cối và chịu thương vong. Họ buộc phải để lại những người bị thương của mình. Khi họ cố gắng lấy lại những người mất tích vào ngày hôm sau, họ lại bị buộc phải rút lui về LZ Cider dưới hỏa lực cối. Đại đội B đã bị tấn công tại địa điểm phục kích của họ bằng tên lửa B-40 và Đại đội D ở LZ D-Handle đã bị các đơn vị công binh tấn công, những người đã phá hủy hai hầm hào bằng hỏa lực tên lửa; cuộc tấn công cuối cùng đã bị đánh bạt bằng hỏa lực pháo binh.Vào ngày 30, Công ty A lại cố gắng tìm kiếm những người mất tích của mình. Họ đã thành công, nhưng buộc phải rút lui một lần nữa khi quân PAVN triển khai pháo cối. Công ty A rút lui và liên kết với Công ty C để đảm bảo một một vị trí an toàn cho đêm. Vị trí này sau đó đã bị đánh bom bởi nhiều cuộc không kích của B-52.Sau khi tiểu đoàn 3/12 rút lui, Tiểu đoàn 1, Trung đoàn Bộ binh 22 đã bị tấn công tại LZ Cider và YA806827 (14.302°N 107.601°E) vào ngày 2 tháng 4. Mục tiêu của họ là đảm bảo "Mục tiêu Đỏ", tổ hợp hầm mà đã buộc Công ty A, 3/12 phải rút lui. Vị trí này đã bị bao vây bởi các đợt pháo binh và hỏa lực từ máy bay trực thăng trong khi 1/22 tiếp tục trinh sát mục tiêu dưới hỏa lực mạnh. Tiểu đoàn 1/22 đã được rút về vào ngày 13 tháng 4 và phần còn lại của tiểu đoàn 3/12 vào ngày 14 tháng 4.

Hậu quảChiến dịch Wayne Grey kết thúc vào ngày 14 tháng 4. Liên đoàn 1, Sư đoàn 4 đã gây thiệt hại nặng nề cho các Trung đoàn Bộ binh 24 và 66 của PAVN và các đơn vị hỗ trợ của họ. Mặc dù PAVN đã có thể rút lui về Campuchia, chiến dịch Wayne Grey được coi là một thành công vì nó ngăn chặn được bất kỳ cuộc tấn công nào ngay lập tức vào Kontum.Vị trí của pháo bị bắt giữTheo các nhân chứng của cuộc tấn công, cụ thể là Trung úy Nolan và Đại úy Yamashita, họ tin rằng nhiệm vụ đã diễn ra ở bên kia biên giới tại Campuchia chứ không phải ở Việt Nam như báo cáo hành động sau và tọa độ bản đồ đã chỉ ra.

Họ giải thích rằng các người lính thuộc Công ty D không được cung cấp tọa độ của vùng hạ cánh hay bản đồ thông thường, mà thay vào đó là những bản đồ địa hình đen trắng cần phải có đào tạo sâu rộng để đọc. Điều này cộng với việc Công ty D phải bay lâu hơn nhiều so với thời gian bình thường cho một chuyến bay với quãng đường đó và có sự khác biệt đáng kể về địa hình, bản đồ cho biết họ đang ở trên một ngọn đồi khi thực tế thì không phải như vậy, tất cả những điều này làm một phần tăng thêm sự nghi ngờ của Nolan và Yamashita. Tám ngày sau khi Công ty D tái chiếm các khẩu pháo và khoảng giữa cuộc chiến, Bộ Tư Lệnh Không Quân Chiến Lược Hoa Kỳ bắt đầu chiến dịch ném bom bí mật chống lại Campuchia.

Tài liệu tham khảoHale, Knight (30 tháng 4, 1969). "Báo cáo Hành động Sau Chiến đấu cho Chiến dịch Wayne Grey" (PDF). ivydragoons.org. Truy cập ngày 30 tháng 8, 2020.Thompson, Lee. "Một Cuộc Chiến Trên Thung Lũng Plei Trap". bravecannons.org/. Truy cập ngày 31 tháng 8, 2020.Nolan, J.L. (1–31 tháng 3, 1969). "Đại đội 4, Công ty D, Tiểu đoàn 1, Trung đoàn Bộ binh 8, D Division, Việt Nam, tháng 11 năm 1968 – tháng 8 năm 1969 J. L. Nolan". swampfox.info. Truy cập ngày 30 tháng 8, 2020.Fisher, Dan. "30 Năm Sau: Một Bí Ẩn Việt Nam". members.tripod.com. Truy cập ngày 30 tháng 8, 2020.Hickey, Pennel (14 tháng 3, 1969). "Báo cáo Hành động Sau Chiến đấu" (PDF). ivydragoons.org. Truy cập ngày 25 tháng 8, 2020.