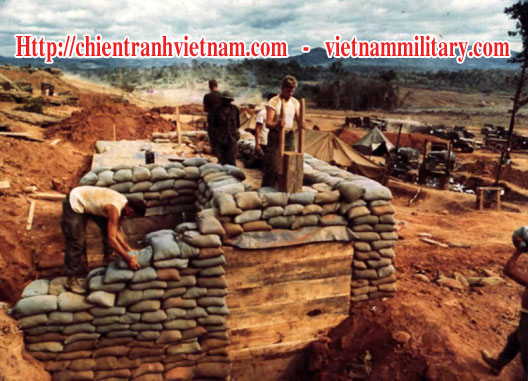

The Battle at Khe Gio Bridge Copyright © 1999, All Rights Reserved From a tactical perspective, the attackers neither damaged the bridge nor dislodged the garrison. But the enemy’s real objective was to inflict American casualties, in the hope of hastening the U.S. withdrawal already underway in northern I Corps, and in pursuit of an overall strategy to win the war in America’s living rooms. To this end, the NVA would accept high relative losses. In another context, the U.S. losses comprised 9% of the 33 Americans killed in Vietnam this day. The enemy profited more, without cost, from the loss of 14 men of the 25th Infantry Division in a non-hostile helicopter accident later in the day. But every loss devastated the families and communities back home and increased the cumulative effect on the U.S. populace, which was growing tired of losing sons. The enemy’s plan was to sneak into the perimeter, pin down the defenders with rocket and mortar fire, and kill them in the bunkers with grenades and explosives. The strength of the assaulting force was in the range of 150 to 400 troops. For the 11 U.S. survivors, 4 of whom would have died if a squad leader had not sacrificed himself to save them from a grenade, it was a terrifying experience. The U.S. casualties were: 2d Lt. Gary Bernard Scull, 30, Advance Team 3, MACV, from Harlan, Iowa, assistant advisor to the 2/2 ARVN Regiment, who by a stroke of incredible bad luck arrived at the bridge only a few hours before it was attacked. He had been in Vietnam since November 1969. Sgt. Mitchell William Stout, 20, C Battery, 1/44 Artillery, from Lenoir City, Tennessee, who was five weeks into his second Vietnam tour, having served previously with 1st Platoon, B/2/47 (Mech), 9th Infantry Division. Sp/4 Terry Lee Moser, 21, also of C/1/44, from Barto, Pennsylvania (a suburb of Philadelphia), who had been in Vietnam nine months and undoubtedly was looking forward to going home. Except for Lt. Scull, the U.S. personnel were from 1/44, an Air Defense Artillery (ADA) battalion attached to 108th Artillery Group and headquartered at 3rd Marine Division’s large base (pop. 30,000) near the village of Dong Ha on Highway 1 north of Quang Tri City. Lt. Col. Richard L. Myers and Capt. Douglas Mehle were the commanding officers of 1/44 and C Battery, respectively. After Khe Sanh was deactivated in 1967, Highway 9 beyond Camp Carroll was kept open to support operations in northwestern I Corps. Khe Gio Bridge, about 20 miles west of Dong Ha, one of 49 bridges on this road, was guarded by two dusters from C/1/44, a searchlight from G/29 (a 1/44 line battery), and 40 or so men of the 2/2 ARVN Regiment. Getting there wasn’t easy because the road went through rugged country, had to be swept for mines, and was subject to ambushes. I made this trip on 28 Sept 1969 and 5 April 1970 riding with a couple tons of ammunition and watching artillery rounds impacting along the road ahead of us. To protect the bridge, the weapons and camp had to abut the road, which followed the low topography through the hilly terrain, giving the high ground advantage to the enemy. Wooded ridges concealed their advance, provided mortar positions looking down on the target, and masked the line-of-sight fire from our dusters. The living quarters occupied a small compound on a hill above a road-cut through a ridge. Vehicles could get up there by a short access road. On the opposite side, an easy slope fell to the river which could be waded nearly everywhere. The defenses consisted of a “cow fence” and apron with limited concertina and some trip flares in the wire. I felt the place was exposed, and have been reminded of it every time I’ve seen the movie "Apocalypse Now". The duster was a powerful weapon. It could fire 240 explosive rounds per minutes to an effective range of 2,000 yards, and unlike field artillery, could rapidly shift fires to engage moving targets. Although obsolete as anti-aircraft weaponry, and not needed in Vietnam for air defense, it was ideal for smashing ground attacks, thus in demand for protecting truck convoys and small firebases such as Khe Gio Bridge. Duster crews had plenty of confidence in their weapon, and the men at the bridge expected the dusters to deter attacks. The weather in early March was scorching and humid with dense fog at night. During the night of March 7, artillery at Quang Tri shot aerial flares to mark a flight path for a medevac mission up north near Gio Linh; the night of March 12 was foggy again, and the NVA columns approaching the bridge were aided by poor visibility. They walked into the camp, reached occupied structures, and were climbing through windows and doors when our guys awoke and began shooting from their bunks. Back at Dong Ha, I was in the radio shack with RTO John Goss when Khe Gio’s perimeter exploded and he received the first distress calls from the bridge. The frantic voice, heavy explosions, and stuttering gunfire mingled with radio static are forever etched in my memory. The time was 1:30 a.m., and nobody at battalion headquarters would get any more sleep that night. The NVA had set up a dozen or more rocket pads and mortar tubes in the surrounding hills, and when the firing began inside the camp, they laid a barrage which killed many of their own men but also pinned the defenders inside the bunkers. A letter I wrote later that day, after hearing four survivors tell their story, states “the rain of shells was so heavy no one could go outside without being killed instantly.” Sgt. Stout, in a bunker down by the road with Jimmy Silva and Robert E. Foster of C/1/44 and Richard E. Dunn and John H. Laughridge of G/29, picked up an enemy grenade and carried it outside where it exploded at the same time a mortar round landed nearby. He died instantly, but this act spared the four other men, who all survived the war and made it home. Moser was killed by a mortar burst during this intense bombardment as he sprinted across open ground for a duster. There were two dusters at the bridge, but an RPG destroyed one before it could be manned. The other got into action after the incoming fire slackened but one of its guns jammed immediately. So the battle was fought with only one of the four 40mm Bofors guns counted on for the defense of the camp. The crew fired until the barrel burned out, which probably didn’t take very long, because with NVA running everywhere and mortars firing from numerous emplacements, it’s a safe bet they were slamming shells into their only gun as fast as they could and firing automatic. During the night, Headquarters Battery was assembled and 50 men were recruited for a reaction force. We were 104 enlisted strength at the time, and all stepped forward. Venturing into pitch darkness to confront enemy forces of unknown strength is nobody’s idea of a good time, but we’d go wherever our guys were in trouble, it’s real basic. The reaction force got ready but never left Dong Ha because the embattled survivors saved themselves. With both dusters out of action, the camp could no longer be defended, so the C/1/44 men shot their way out and fled to Camp Carroll two miles away. Some escaped on a deuce-and-a-half, whose driver had been hit and slumped unconscious over the wheel upon getting there. Someone drove the duster through the camp under fire picking up wounded, then crashed the perimeter at Camp Carroll, where the vehicle was seen in the morning draped with barbed wire. The battle had lasted three hours, and the enemy hurried off the battlefield leaving some of their dead, as they wanted to get away before daylight brought jets and gunships. An officer’s daily log entry by Major David W. Wagner, the S-3, identifies the dusters in the battle as C-122 and C-142. The destroyed duster probably was C-122, which is recorded in unit records as a “total loss,” so the fighting duster (and the one reaching Camp Carroll) must have been C-142, which was booked as “salvage” and used for parts. An ARVN company with U.S. advisers who reached the camp at 0700 searched in vain for signs of Lt. Scull. A detail from Dong Ha arriving at 0845 reported finding “enemy 14 KIA and still counting.” My letter states they recovered 17 NVA bodies and estimated from drag marks that 40 enemy troops died inside the perimeter. This number is based on statements made to me by witnesses. I’ve heard claims, then and recently, that ARVNs had shot at Americans; but when the battlefield was seen in daylight, ARVN and NVA bodies were found on top of each other, indicating they had fought to the death in hand-to-hand struggles. The camp itself was a shambles and had to be completely rebuilt. I visited Khe Gio Bridge again three weeks after the battle. It was considerably beefed up with more wire, especially concertina, overhead cover for gun pits, and two replacement dusters. The tenants were understandably nervous, but this was locking the barn after the horse is gone. The NVA did not risk impulsive attacks; they spent weeks or months planning and rehearsing this type of operation. At that moment, Khe Gio Bridge probably was the safest place in I Corps. We eventually turned it over to the ARVNs, who ran like hell, and the NVA recorded their deed without a fight. You can go there as a tourist now, but Highway 9 is still primitive and infrequently traveled. The wartime bridge and camp are gone. I don’t know if there is any trace of the battle, but I’m tempted to wonder whether ghosts of the 48 people who died there return on dark, foggy nights. The survivors who returned to Dong Ha on March 12 thought Lt. Scull was killed in the fight, but an ARVN officer reported his bunker was hit and on fire, and he was led away by NVA soldiers. U.S. intelligence analysts concluded that a report by a former NVA officer in December 1974 about a U.S. POW he saw in June 1971 matched Lt. Scull’s disappearance in terms of description and incident. Nothing else has been learned of his fate. On October 16, 1978, the U.S. Government changed Lt. Scull’s status from “missing” to “died while missing” and upgraded his rank to Major, as was always done for MIAs to maximize government benefits to their families. He is survived by his mother and sister. A memorial web site and photo may be seen at http://geckocountry.com/scull.htm Rumors started circulating at 1/44 headquarters before the sun had set on the day of battle that Sgt. Stout would be recommended for the Medal of Honor. Lt. Col. Myers signed the paperwork, and Jack Stout and Faye Thomas went to Blair House on July 17, 1974, during the last days of the Nixon Administration, to accept their son's medal from Vice President Ford. Jack Stout donated it in 1991 to the National Medal of Honor Museum, where it is on permanent display. Buddy White, a childhood friend, organized a fundraising drive and Mitch's home town built a hero's monument over his grave. A major building at Fort Bliss is named for him, along with the I-75 bridge across the Tennessee River and the Mitchell W. Stout Medal of Honor Memorial Golf Tournament, an annual event in Lenoir City. He also is survived by two sisters. A memorial web page may be seen at https://members.tripod.com/~msg_fisher/moh.html I am seeking information about Sp/4 Terry Moser. I'm proud to have served in 1/44 with the men who fought at Khe Gio Bridge and other battles in the Vietnam War's most honored artillery battalion. My time with them shaped my character and life. Sources and acknowledgements: The author served with HHB/1/44 as the intelligence and operations clerk and other duties as assigned from April 1969 to May 1970. The author's letter of March 12, 1970 describing the battle is a primary source of material for this article; a copy has been donated to the National Medal of Honor Museum. The author was a newspaper reporter before the war and for the last 25 years has been a lawyer residing in Seattle, Washington. The following individuals cooperated in providing information, photographs, and contacts: Gary Puro of the National Dusters, Quads, and Searchlights Association; Ed Hooper of the Tennessee Star Journal and National Medal of Honor Museum; the Harlan (Iowa) Tribune News, Col. Dave Althoff (USAF, retired), Harold "Doc" Peterson (2/47 Mech, 9th Infantry Division), M/Sgt Danny L. Fisher (USA, Retired), John Goss (HHB/1/44), Ben Johnson and Windell Crowell (C/1/44) (military ranks are given where known). I sincerely apologize if I inadvertently left anyone out. Research of this story is an ongoing project and anyone knowing the names of battle participants, possessing photographs of the camp and battle area, or any information about the battle is encouraged to contact the author at dwitt@ctr.net Brief excerpts may be quoted for non-profit educational, scholarly, or historical purposes.

|

b.PNG)

.PNG)