Chiến Đoàn B/TQLCVN hành quân An Lão 1967

MX Tôn Thất Soạn MX Tôn Thất Soạn

I. Tổng quát: Thung lũng An Lão thuôc tỉnh Bình Định, nối dài với thung lũng Vĩnh Thạnh rồi đi qua đèo An Khê, hoặc đổ ra Tam Quan, thuôc quận Bồng Sơn để ra tận bờ biền ở phía Đông. Vì địa thế có vị trí chiến lược quan trọng, nên QLVNCH đã cho thành lập Chi Khu An Lão, cách quận lỵ Bồng Sơn 25 cây số về hướng Tây Bắc; mục đích ngân chận sự xâm nhập của các lực lượng cộng sản từ các mật khu ở ngã ba Biên Giới, mật khu Đỗ Xá ... xuống vùng đồng bằng trù phú và đông dân cư của tỉnh Bình Định.

Chấp hành chủ trương của Bộ chính trị ngày 11-10-1964, các lực lượng cộng sản được lịnh mở chiến dịch mùa khô hay Thu Đông 1964-1965.

Song song với trận Bình Giả ở tỉnh Phước Tuy, tại tỉnh Bình Định, lực lượng cộng sản trong đếm 6-12-1964 đã tấn công đồng loạt cao điểm 193 (nơi đặt vị trí 2 khẩu pháo binh 105 ly), các đồn Địa Phương Quân (ĐPQ) Vạn Khánh, Hội Long và Mỹ Thành...

Qua ngày hôm sau, Sư Đoàn 22 Bộ Binh đã tổ chức cuộc hành quân tiếp viện gồm cánh Trực Thăng Vận, Thiết Quân Vận có Bộ Binh tùng thiết và cánh di chuyển bộ xuất phát từ Bồng Sơn... Ba cánh quân đều chạm địch. Cả hai phía đều bị thiệt hại. Lực lượng cộng sản trước tình hình bất lợi nên đã rút lui trong ngày 9-12. Về phần QLVNCH, thấy không đủ lược lượng để bảo vệ một khu vực với địa thế phức tạp và cô lập này, nên sau cùng cũng đã bỏ rơi vùng An Lão này.

Giữa năm 1965, Chiến Đoàn A-TQLC của Trung Tá Nguyễn Thành Yên CĐT, và Thiếu Tá Cổ Tấn Tinh Châu TMT/CĐ, cùng với Tiểu Đoàn 1/TQLC do Thiếu Tá Tôn Thất Soạn TĐT và Tiểu Đoàn 3/TQLC của Thiếu Tá Nguyễn Thế Lương TĐT, đã tham dự cuộc hành quân tìm và diệt địch tại thung lũng An Lão. TĐ1 đã tiến chiếm mục tiêu đồi 193, có tên địa phương là đồi Thánh Giá, vì có xây cất một Thánh Giá kích thước rất lớn bằng bê-tông cốt-sắt, sơn màu trắng xóa, sừng sửng trên cao, giữa nền xanh biết của núi non, hiểm trở.

Ngày 28-1-1966, QLVNCH phối hợp hành quân với các lực lượng của 1st CAV (Sư Đoàn 1 Kỵ Binh Không Vận Hoa Kỳ hay gọi tắt Không Kỵ Hoa Kỳ) mở cuộc hành quân có tên là Masher / White Wing, còn được gọi là Chiến Dịch Bồng Sơn. Chiến dịch kéo dài trong 42 ngày tại quận Đức Phổ tỉnh Quảng Ngải với lực lượng TQLC Hoa Kỳ tại thung lũng An Lão và thung lũng Kim Sơn thuộc tỉnh Bình Định với KBKV-HK.

Tổng kết về thiệt hại nhân mạng gồm 1,342 quân cộng sản tử trận, 635 tù binh, 1087 tình nghi bị bắt giữ... Tuy nhiên đã khiến 3,421 dân chúng trở thành nạn nhân chiến cuộc.

II. Tổ chức lực lượng Chiến Đoàn B/TQLC/VN II. Tổ chức lực lượng Chiến Đoàn B/TQLC/VN A. Bộ Chỉ Huy Chiến Đoàn:

- Chiến Đoàn Trưởng: Trung Tá Tôn Thất Soạn (Sài-Gòn)

- Cố Vấn Trưởng: Thiếu Tá Larry Gaboury

- Cố Vấn Phó: Đại Úy John Grinalds (1)

B. Tiểu Đoàn 2/TQLC:

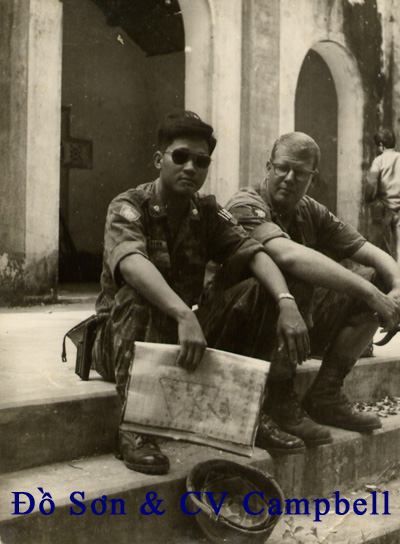

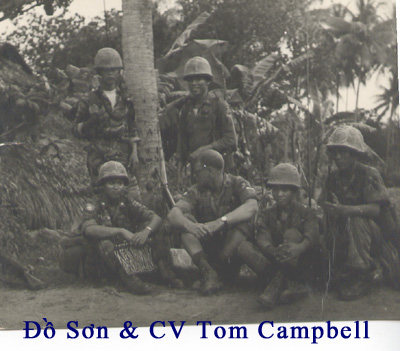

- Tiểu Đoàn Trưởng: Thiếu Tá Ngô Văn Định (Đồ-Sơn)

- Tiểu Đoàn Phó: Đại Úy Nguyễn Kim Đễ (Đà-Lạt)

- ĐĐT/ĐĐ/CH: Trung Úy Trần Kim Đệ

- ĐĐT/ĐĐ1: Đại Úy Trần Kim Hoàng

- ĐĐT/ĐĐ2: Trung Úy Trần Văn Thuật

- ĐĐT/ĐĐ3: Trung Úy Đinh Xuân Lãm

- ĐĐT/ĐĐ4: Trung Úy Trần Văn Hợp

- Cố Vấn Trưởng: Đại Úy Thomas Campbell

C. Tiểu Đoàn 3/TQLC:

- Tiểu Đoàn Trưởng: Thiếu Tá Nguyễn Năng Bảo (Bắc-Ninh)

- Tiểu Đoàn Phó: Đại Úy Phạm Văn Sắt

- ĐĐT/ĐĐ/CH: Trung Úy Nguyễn văn Bằng

- ĐĐT/ĐĐ1: Trung Úy Dương Văn Hưng

- ĐĐT/ĐĐ2: Trung Úy Lê Bá Bình

- ĐĐT/ĐĐ3: Trung Úy Hoàng Đôn Tuấn

- ĐĐT/ĐĐ4: Trung Úy Vũ Mạnh Hùng (Tử trận Tết Mậu Thân, cầu Bình Lợi)

- Cố Vấn Trưởng: Đại Úy Mac Dube (2)

D. Pháo Đội 105 ly TQLC:

- Pháo Đội Trưởng: Đại Úy Trần Thiện Hiệu

III. Phương tiện yểm trợ:

- Pháo Binh: Ngoài pháo đội 105 ly TQLC đặt tại phi trường Đệ Đức, còn có thêm 2 khẩu 155 ly của SĐ22/BB đặt tại phi trường Bồng Sơn và còn có những pháo đội 105 ly của Kỵ Binh Không Vận (KBKV) HK đặt rải rác trên các cao điểm trong vùng hành quân để yểm trợ cho CĐ-B/TQLC khi có yêu cầu.

- Không Quân: Có L-19 US-FAC bao vùng và hướng dẫn các phi tuần của Không Quân HK cũng như trực thăng của Kỵ Binh Không Vận HK khi nhận được yêu cầu qua hệ thống Cố Vấn Mỹ.

IV. Nhiệm vụ của CĐ-B/TQLC: Vào ngày N giờ G của trung tuần tháng 3-1967, CĐ-B/TQLC tổ chức cuộc hành quân “Tìm và Diệt” các đơn vị CSBV cấp tiểu đoàn đang ẩn núp trong khu vực thung lũng An Lão, tiếp theo sau khi đơn vị 1st CAV (KBKV) HK rời khỏi vùng An Lão.

Nhiệm vụ kế tiếp là di chuyển tất cả dân cư trong khu vực An Lão đem về định cự tại các trại tỵ nạn cộng sản ở khu vực Bồng Sơn.

V. Diễn tiến: Lúc 4 giờ sáng ngày N, Chiến Đoàn xuất phát từ vị trí đóng quân đêm ở phí Bắc Quận Lỵ Bồng Sơn di chuyển về hướng Bắc, dọc theo sông An Lão. TĐ3 cánh trái, TĐ2 cánh phải của bờ sông. BCH/CĐ di chuyển cùng với TĐ2. Hai cánh quân di chuyển song song và theo thế chân vạc để yểm trợ lẫn nhau.

Khi các cánh quân sắp sửa vào vùng mục tiêu (MT) đầu tiên, thì L-19 Mỹ với FAC (Sĩ Quan điều không tiền tuyến) Larry Pritchett báo cho Đại Úy Mac Dube:

- Hãy cẩn thận, có người di chuyển ở dãy triền đồi trước mặt của các anh.

Vừa nói xong, thì TĐ3 bị các tràng đạn của địch từ cao điểm bắn xuống. Bắc-Ninh liền điều động các Đại Đội tìm chỗ ẩn nấp dọc theo rặng cây và hốc đá sát chân núi..., tránh những nơi cát trống ngoài bờ sông. Lúc này TĐ2 còn cách mục tiêu trước mặt lối 400m và cách 600m về phía Đông của TĐ3. TĐ3 bắt đầu gọi pháo binh bắn vào cao điểm có địch bố trí, và tiếp đến là các phi tuần cánh quạt được FAC hướng dẫn đánh tiếp vào mục tiêu.

TĐ3 bắt đầu tiến quân sát chân núi, chẳng được bao lâu thì bị địch ở các cao điểm khác tác xạ xuống đoàn quân bằng thượng liên và súng trường... Địch có lợi thế vì chúng nấp và các hang động, mỏm tảng đá, mỗi khi ta bắn pháo binh hay oanh kích, không có hiệu quả!?

Lúc này, dân chúng trong làng bên hông của TĐ2 bắt đầu gồng gánh đồ đạt và bồng bế trẻ con ra khỏi làng và xuôi Nam về hướng Bồng Sơn. Đồ-Sơn gởi một Trung Đội đến chận xét và hỏi han thì được báo là có một đơn vị chính quy cộng sản đang bố trí trong làng phía trước mặt TĐ2. Vì sợ bom đạn của hai bên sẽ đánh nhau, nên họ phải tránh về vùng an ninh để khỏi bị thiệt hại.

Mặc dù di chuyển đội hình rất cẩn thận, nhưng TĐ3 vẫn bị các chốt của địch trên đồi cao bắn chận nhiều lần khiến ta có vài quân nhân bị thương.

Để tránh thiệt hại về nhân mạng, TĐ3 được lệnh bố trí tại chỗ, chờ trời tối tìm cách tiến quân để tránh sự quan sát của địch và tìm cách bộc hậu chúng... Đồng thời TĐ2 cũng được lệnh bố trí tại chỗ, chờ pháo binh và không quân bắn tiêu diệt vào mục tiêu có đơn vị địch bố trí trước khi có lệnh tấn công, lục soát...

Sài-Gòn yêu cầu Thiếu Tá Gaboury can thiệp để xin không quân HK (KQHK) oanh kích vào mục tiêu cho cánh TĐ2. L-19 FAC của KQHK tận tình điều chỉnh 20 phi tuần dội bom xuống các vị trí nghi ngờ địch bố trí trong mục tiêu. Trời bắt đầu tối, FAC điều động thêm “con rồng lửa” AC-130 tàn sát mục tiêu, tiếp bằng các tràng đại liên và thả hỏa châu để phi cơ oanh kích rõ các nơi có địch. Chấm dứt các phi tuần yển trợ, pháo binh KBKV được điều chỉnh bắn quấy rối suốt đêm để ngăn chận địch tẩu thoát về hướng Bắc.

Trời bắt đầu hừng sáng của ngày N + 1, TĐ2 đã xin bắn 1 loạt pháo 105 ly đạn khói để làm màn che giữa bìa mục tiêu và vị trí dàn quân chuẩn bị tấn công của các chiến sĩ Trâu Điên. Màn khói vừa chấm dứt, các Trâu Điên đã tràn lên xung phong vào mục tiêu. TĐ2 chiếm mục tiêu một cách dễ dàng vì đã bị bỏ trống, chỉ còn những chốt cố thủ của địch rải rác trong mục tiêu. Tiến súng nổ vẫn thỉnh thoảng nổ liên hồi, xen kẻ giữa tiếng AK47 và M16 cũng như tiếng lựu đạn của quân ta ném vào hầm hố phòng thủ của địch. Có nơi quân ta phải đánh cận chiến với địch vì chúng liều chết không chịu đầu hàng.

TĐ2 có tất cà 17 quân nhân bị thương và tử thương, trong đó 1 sĩ quan tử trận. Tiếng súng đã ngừng hẳn vào trưa ngày N + 1. Trực thăng tải thương của KBKV đã nhanh chóng bốc 3 chuyến là hoàn tất. Các Đại Đội bắt đầu phân tán lục soát kỹ hầm hố của địch. Kết qủa ta bắt sống 3 tù binh bị thương, 10 tên bỏ xác tại chỗ, tịch thu 12 khẩu súng cá nhân cùng vật dụng và tài liệu của địch. Một trong số tử thi có cuốn sổ nhật ký, đương sự là Đại Đội Trưởng ĐĐ Phòng Không CSBV. Sổ nhật ký nghi rõ, ĐĐ đã bị mất 2 khẩu 12 ly 7 trong tháng trước khi bị một đơn vị “Lính Thủy Đánh Bộ Mỹ” hành quân chận đánh ở Quận Đức Phổ, Tỉnh Quảng Ngải.

Địch phân tán lực lượng để tẩu thoát về hướng Bắc, chỉ để lại 16 tên với cán bộ Đại Đội Trưởng (ĐĐT) này để cầm chân đơn vị QLVNCH, và quyết tử thủ cho đến viên đạn cuối cùng.

Khi các chiến sĩ Trâu Điên xung phong vào vị trí cố thủ của tên ĐĐT này, thì y đứng bật dậy, chỉa khẩu K54 bắn chết 1 TQLC và làm bị thương 2 TQLC khác, trước khi y bị các Cọp Biển bắn hạ... Sau đó, Đồ-Sơn ra lệnh cho anh em chôn cất các tử thi địch một cách tử tế.

TĐ2 tiếp tục lục soát các mục tiêu cuối về hướng Bắc, không còn gặp sự kháng cự nào của địch. Tuy nhiên, ta phát giác đường di chuyển của địch và rơi rớt các quân dụng và băng bó có dính máu, chứng tỏ chúng rút chạy có mang theo thương binh...

TĐ2 được lệnh trở lại lục soát tiếp các MT cũ và bố trí quân tại MT sáng ngày N + 1 để yểm trợ TĐ3 bắt đầu tiến quân lục soát các MT được chỉ định theo phóng đồ.

Sáng sớm ngày N + 1, sau khi TĐ3 lợi dụng bóng đêm ngày N, đã bọc hậu sau lưng vị trí chốt của địch, và tiến lên lục soát MT mà đã được pháo binh và không quân oanh kích trong ngày N đầu tiên. TĐ3 tìm thấy 3 tử thi VC tạm nguyên dạng và vài tử thi khác nát từng mảng, ước lượng khoảng 1 tiểu đội. Không tìm thấy vũ khí, chỉ thấy những mảnh kim loại của các vũ khí cá nhân... Ngoài ra còn 2 vị trí khác không thể ước lượng vì những đợt bom đã đè sập các hốc đá... TĐ3 tiếp tục tiến quân vào các MT nghi ngờ kế tiếp. Khi TĐ3 đi ngang hàng so với vị trí của TĐ2 đang bố trí phía bờ Đông của sông An Lão, thì có L-19, do Trung Úy phi công Phil Jones (3) bay vào không phận để làm việc với Cố Vấn Chiến Đoàn B. Thiếu Tá Larry Gabaury, đã chuyển cho Đại Úy Mac xử dụng. Sau khi trao đổi tình hình, Mac yêu cầu Phil quan sát kỷ trên đồi trước mặt của TĐ3 đang tiến quân!

L-19 vừa đảo một vòng thấp để quan sát MT, bổng có những loạt phòng không 12 ly 7 nổ dòn từ hướng đỉnh đồi lên phi cơ. Tiếng máy động cơ L-19 bổng nghe nổ “lụp bụp” như muốn “khựng” lại, sau đó là tắt hẳn, không nghe gì cả!? Im lặng trong chốc lát, bổng có tiếng nói hốt hoảng của Phil vang lên trên máy truyền tin không-lục:

- Phi cơ đã bị trúng đạn! Tôi đang đáp xuống đây!

Phil đáp khẩn cấp xuống bải cát trống và bằng phẳng bên bờ sông, đàng sau đoàn quân TĐ3 đang di chuyển. Mặc dù Phil cố gắng điều khiển máy bay bị tắt máy xuống an toàn, nhưng vì lao xuống quá mạnh, 2 bánh xe lún xuống bải cát, nên sức bật đã làm máy bay lật ngược phần đuôi và thân bật ra đằng trước! Có khói bốc ra từ động cơ, nhưng may mắn chưa bắt lửa! Cảnh tượng này đột ngột xảy ra trước mắt các Cọp Biển, vì 2 bên bờ sông là những bải cát trống trải không có cây cối nào cả. Phil hơi bị “sốc” một chút, nhưng vẫn còn tỉnh tảo và an toàn.

Lập tức Đ/U Mac và Hạ Sĩ Cước, hiệu thính viên truyền tin hộc tốc chạy đến nơi L-19 rơi. Tiếp theo đó, Bắc -Ninh liền cho một tiểu đội chạy theo để bảo vệ Mac và Phil cùng chiếc L-19. Chốt địch trên đồi cao tiếp tục bắn sẻ xuống khu vực có L-19 rớt, may mắn chưa có ai bị trúng thương cả. Để tránh địch bắn vào toán cứu nạn L-19, Đồ-Sơn và Bắc-Ninh ra lệnh cho vài khẩu đại liên M60 và súng cối 80 ly thỉnh thoảng bắn đàn áp lên đỉnh đồi để địch không ngóc đầu lên được. Khi đến sát chiếc L-19, Mac lưu ý Phil cởi bỏ chiếc nón bay màu trắng ra, vì đó là mục tiêu dễ nhìn của toán bắn sẻ VC. Mac đồng thời loay hoay tháo gỡ 4 hỏa tiển còn gắng trên L-19 để khỏi lọt vào tay địch. Chúng có thể lấy và biến chế làm mìn bẩy sau này... Khoảng nửa giờ sau được cấp báo từ CĐ-B, 1 chiếc CH47 đến câu chiếc L-19 bị nạn; Mac và Phil phụ móc dây vào thân L-19 để câu về phi trường Bồng Sơn an toàn... Chẳng bao lâu thì có 1 trực thăng tản thương đến bốc Phil. Sẵn dịp này, Mac cũng nhận được lệnh của Thiếu Tá Gaboury cho Mac cùng lên máy bay với Phil để về Bồng Sơn. Lý do là Mac đã nhận được lệnh mãn nhiệm kỳ sau 1 năm phục vụ ở Việt Nam, trước 1 ngày khi có lệnh hành quân của Chiến Đoàn B. Tuy nhiên vì chưa có sĩ quan thay thế nên Mac tình nguyện đi theo TĐ3 cho hết cuôc hành quân An Lão này. Nhưng nay đã có người thay thế Đ/U Mac... Hôm nay là một ngày trọng đại đối với CV Mac Dube USMC, trong nhiệm kỳ phục vụ ở VN. Ngoài ra phải khâm phục sự hăng say nhiệt tình trong phận sự và lòng can đảm của một quân nhân TQLC-HK như Mac, khi bất chấp các lằn đạn bắn sẻ của địch từ trên đỉnh đồi cao, vẫn nhanh nhẹn chạy đi cứu phi công Phil, vẫn bình tĩnh đứng phụ móc dây "cáp" để CH47 câu chiếc L-19 bị nạn, vẫn thong thả đứng tháo 4 hỏa tiển gắn chặt trên L-19, hòng sợ lọt vào tay địch...

Sau đó, CĐ-B xin các phi tuần đến oanh kích vào các cao điểm địch đống chốt, tiếp theo là những đợt pháo binh bắn đạn nổ chậm, và cuối cùng là đợt đạn khói để làm màn che, không cho địch quan sát xuống; Đoàn quân TĐ3 tiếp tục tiến quân lục soát về hướng Bắc và không còn bị địch tác xạ nữa...

TĐ2 và TĐ3 tiếp tục lục soát các MT xóm làng, đồng thời hô hào dân chúng di tản khỏi khu vực An Lão theo lệnh hành quân của SĐ22/BB. Đa số dân chúng sau khi được các đơn vị TQLC tập trung từ khu vực, được CH-47 của KBKV lần lượt không tải về phi trường Bồng Sơn, ở đấy đã có các toán tiếp đón của Quận hành chánh Bồng Sơn phụ trách. Dân chúng được đưa vào tạm trú tại các nơi được gọi là “trại định cư tỵ nạn chiến tranh”. Có 1 giai thoại đáng kể lúc này là có 1 bà già, miệng ăn trầu cau, vừa khóc lóc và từ chối lên máy bay chở đi. Bà ta kể lể: “Thà bị bắn chết tại chỗ, còn hơn bị lùa vào trại tỵ nạn”. Hiện bà ta “tứ cố vô thân”, không muốn lìa xa quê hương xứ sở, mồ mả ông bà! Có 2 anh em Mũ Xanh đứng gần đó, giải thích với bà ta và vội vàng đở bà ta lên trực thăng để làm tròn nhiện vụ “bắt buộc nhưng không vui tí nào!”

Cuộc hành quân chấm dứt vào ngày N+2, sau khi CĐ-B đã hoàn thành nhiệm vụ “di chuyển toàn thể cư dân trong thung lũng An Lão ra định cư ở Bồng Sơn”. Chiến Đoàn di chuyển bộ, lục soát dọc theo sông An Lão, xuôi Nam để ra vùng tập trung ở Quận Lỵ Bồng Sơn. VI. Nhận Xét: 1. Thung lũng An Lão, luôn luôn là mục tiêu tranh chấp giữa ta và địch trong suốt cuôc chiến tranh vừa qua; Được bao bọc giữa 2 dãy núi cao, là đường xâm nhập từ các mật khu Đỗ Xá, Ba Biên Giới ở Tây Nguyên... xuyên qua Tam Quan để đi ra tận vùng duyên hải ở phía Đông. CSVN đã tự hào rằng trong suốt 9 năm chiến tranh Việt-Pháp, An Lão là một mật khu an toàn nhất của chúng. Chúng thường truyền khẩu trong dân địa phương rằng: “Suối Đỏ ai qua là bỏ mạng!”, ý muốn nói không sống mà trở về được; Con suối này chảy vào đầu nguồn của sông An Lão.

2. Không riêng gì các chiến sĩ TQLC đều biết rằng tình Bình Định nguyên thuộc Liên Khu 5 trong thời chiến tranh Việt-Pháp, từ lâu là vùng nổi tiếng chịu ảnh hưởng của cộng sản; Đến nỗi những quân nhân thuôc đơn vị KBKV Mỹ cũng thốt lên rằng vùng thung lũng An Lão và thung lũng Kim Sơn là những hiểm địa đã từng xảy ra các trận đụng độ ác liệt với quân đội VNCH và đã gây tổn thất nặng nề cho cả hai phía.

3. Sau chiến thắng Phụng Du ngày 7/4/65 của Chiến Đoàn A TQLC cùng với TĐ1 và TĐ2, thì từ đó cho đến năm 1967, hai Chiến Đoàn A & B TQLC hầu như luân phiên nhau, thường trực hoạt động hành quân ở vùng đồi 10, Tam Quan, An Lão, Bồng Sơn... Đặc biệt trong đầu năm 1967, CĐ-B hoạt động ở vùng Dương Liểu, Đầm Trà Ổ thuộc quận Phù Mỹ đã được sự yểm trợ dồi dào của 1st CAV về trực thăng vận cũng như không pháo yểm trợ.

4. Sư Đoàn 3 Sao Vàng VC đã nếm mùi thất bại khi đụng độ với các đon vị Cọp Biển, như trận Phụng Du năm 1965, cho nên chúng thường né tránh như cuộc giải vây áp lực địch ở quận Hoài Ân năm 1966 của CĐ-B/TQLC.

5. Trong trận An Lão lần này, trước khi dàn quân vào MT đầu tiên, Đồ-Sơn quan sát thấy 1 đơn vị địch đang di chuyển từ trên triền núi xuống. Đồ-Sơn xin Sài-Gòn cho bắn pháo binh, nhưng vì núi có nhiều hốc đá, nên bắn pháo binh không có hiệu quả bao nhiêu. CĐ-B yêu cầu hệ thống CV Mỹ cho không quân oanh kích, nhưng cũng không được thỏa mãn. Lý do, FAC không thấy súng phòng không địch bắn lên!?

Sau khi chiếm MT ở An Lão, TĐ2 bắt được một số tù binh thuộc đơn vị chính quy Bắc Việt.

6. Đêm ngày N, BCH/TĐ2 đóng quân trong MT xóm nhà dân, khi đon vị lục soát xong, Đồ-Sơn trải tấm “poncho” ngủ trong một căn nhà lá. Nửa đêm nghe tiếng động dưới mặt đất, lúc đầu tưởng là chuột chạy! Nhưng cũng sinh nghi, vội gọi “đệ tử” vào lục tìm xem! Thì phát giác ra được 1 nắp hầm bí mật được ngụy trang khéo léo dưới gầm giường. Bật nấp hầm lên, thì ra là 1 tên lính CQBV, mặc quân phục màu xanh dương trốn dưới hầm. May quá, nếu tên này có sẳn vũ khí, hay lựu đạn mang theo bên mình thì thật là nguy hiểm!.

7. Trưa ngày N + 1, sau khi TĐ2 thanh toán và lục soát xong MT mà có địch bố trí phòng thủ để chận đường tiến quân của ta; thì cánh B/TĐ2 được lệnh tiến quân lục soát tiếp các xóm làng về hướng Bắc. Nhưng một lúc sau thì thấy các Trâu Điên bỏ chạy tán loạn ngược về hướng Nam, Đồ-Sơn lấy làm ngạc nhiên, vội bốc máy hỏi thì được Đà-Lạt, TĐP báo cáo là có tổ ông “vò vẽ” đang rượt đánh các Trâu Điên. Trâu Điên mà gặp ông vò vẽ thì cũng đành chịu thua luôn...!

8. Cuộc hành quân càn quét địch ở thung lũng An Lão với mục đích đưa dân ra định cư ở vùng an ninh Bồng Sơn, trong các trại định cư tỵ nạn cộng sản đã không mang lại kết quả tốt đẹp như mong muốn. Mặc dù có ngân khoản của Mỹ đài thọ cho chương trình định cư tỵ nạn chiến tranh, nhưng số lượng rất hạn chế và chỉ tạm thời trong một thời gian ngắn. Sau đó, vì không được chính quyền địa phương chăm sóc chu đáo, nên những người dân này lần lượt trở về lại quê hương xóm làng cũ để sinh sống; Mặc dù họ biết rồi đây sẽ phải gánh chịu một cổ mà hai tròng - Cộng Sản lẫn Quốc Gia!.

MX Tôn Thất Soạn

Iowa City, 2005

Tài liệu tham khảo:

1. Dr. Phương Nguyễn, Chiến tranh VN toàn tập, NXB Làng Văn 2000

2. Col. Thomas Campbell, USMC Ret., My War.... Vietnam, 2005

Phụ chú:

(1) - John Grinalds:

Tháng 3 năm 1967, Đại Úy USMC John Grinalds là Cố Vấn phó Chiến Đoàn B/TQLC của Trung Tá Tôn Thất Soạn, tham dự cuộc hành quân An Lão. John có cuộc đời binh nghiệp rất sáng chói. John có sở trường giải quyết mọi khó khăn trong công việc một cách khéo léo và ổn thỏa kỳ lạ. John có tính kiên nhẫn và có tài điều hợp mọi vấn đề. John giải ngủ với cấp bậc Thiếu Tướng (Major General). Bà vợ Norwood có biệt tài về nấu nướng...

(2) – Marcel (Mac) Jacques Dube:

Năm 1967, Đại Úy Mac Dube, USMC là Cố Vấn trưởng TĐ3/TQLC cho Thiếu Tá Nguyễn Năng Bảo. Tham dự cuộc hành quân An Lão, Bồng Sơn tỉnh Bình Định, Việt Nam cùng với Chiến Đoàn B/TQLC. Mac Dube là một trong hai người dũng cảm nhất mà tôi (Campbell) biết được. Mac từng phục vụ 4 hoặc 5 năm trong thời gian chiến tranh tại Việt Nam với nhiều nhiệm sở khác nhau. Mac và tôi cũng từng phục vụ với nhau tại trường chỉ huy và Tham Mưu TQLC Mỹ (US Marine Corps Command & Staff College) tại Quantico, Virginia. USA. Mac về hưu ở cấp bậc Đại Tá và về định cư ở 29 Palms; California. Từ đó, anh ta theo học trường Luật một thời gian và trở thành Thị Trưởng xuất sắc và làm cố vấn cho Thành Phố!

Mac kết hôn với Pat trong hạnh phúc...

(3) – Phil Jones:

Trung Uý phi công USAF lái L-19 trong cuộc hành quân An Lão cùng CĐ-B năm 1967. Về sau Phil giải ngủ và lái máy bay cho hãng Delta Airlines; Sau cùng là lái máy bay tuần tra biên giới Mỹ (Border Patrol Official)

|

MX Tôn Thất Soạn

MX Tôn Thất Soạn

II. Tổ chức lực lượng Chiến Đoàn B/TQLC/VN

II. Tổ chức lực lượng Chiến Đoàn B/TQLC/VN